Meiji and Modernisation

Commodore Perry and the end of Sakoku (Isolation)

During the 16th Century European traders began to arrive in Japan, originally starting with a group of Portugese traders shipwrecked on their way to the Phillipines. Christianity had begun to spread with the arrival of missionaries and later would influence daimyo Sumitada Omura who converted to Catholicism. He helped the Dutch and Portugese traders establish a base in Nagasaki however the Shogun fearing the influence of the missionaries and the message of Christian peace moved the traders to an artificial island in the bay of Nagasaki. Religious influences had historically been seen as suspicious by the Shogunate due to the serious threat of militant Buddhist monks during the Sengoku “warring states” period prior to the unification of Japan. A peasant uprising against the local authorities broke out in the primarily Christian populations of Shimabara & Karatsu – unrelated to religion but instead to the local living conditions and bakufu taxation. Nonetheless the Shogunate declared a Sakoku “Locked Country” era to reduce the influence of the Christian empires of Portugal and Spain. Japanese citizens were banned from leaving the country and trade with other nations was restricted to government controlled paths with the Dutch, Ainu (Hokkaido natives), Koreans & Ryukyu independents. Dutch traders were allowed only onto the isolated Nagasaki island of Dejima. This effectively cut off all outside cultural influences and trading opportunity allowing Japan to fall into strictly controlled but peaceful times during the Edo period.

The Sokaku period lasted from 1637 – 1852 when Commodore Perry led an American expedition to Japan. With the country locked to foreigners Japan had no reason to invest in a naval military force and the arrival of “The Black Ships” – 4 well stocked warships from America could not be met with Japanese hostile response. Perry though threatening in his manner arrived on a mission of peace and presented letters from the then US President Millard Fillmore to the Emperor of Japan proposing a friendly treaty. Perry was allowed to return to the United States with promises of international friendship and would eventually return a year later when a formal treaty – the Convention of Kanagawa (1854) – was entered into.

This marked the end of the national isolation and opened ports in Shimoda and Hakodate to American trade. The process was not a smooth one though and the agreement guaranteed no foreign residencies only trade. It wasn’t until the arrival of diplomat Townsend Harris that the Treaty of Amity and Commerce guaranteed not only trade but also diplomatic exchange and foreign extraterritoriality – ensuring that American Citizens were subject to American and not Japanese law while in Japan. The Japanese government was dubious about the process but nervous about the recent colonial subjugation of China by the British and signed the agreement hoping to avoid similar warfare. The Harris Treaty became the first of a series – the Ansei Treaties – that would further open relations with Britain, Russia, Netherlands and France.

During his stay Harris would have his own geisha dalliance with a young girl called Okichi – supposedly pressured into the relationship to ease agreements with Harris. While the relationship was supposedly amicable Okichi was ostracised after Harris returned to the United States and would later commit suicide. Though little was written at the time on the details of the affair it would later be romanticised into the John Wayne film “The Barbarian and the Geisha”

Meiji Restoration

The Japanese had seen for themselves that the Sakoku period had given Western nations a great technological advantage in ships, guns and steel. Growing unrest in the population over the limited external communication and the inability of Japanese to learn from their foreign trade partners had many concerned. As well as a greater desire within the civilian population to increase trade and technological education the authorities wanted to restore Imperial rule claiming that this would strengthen Japan against the potential threat of colonialism.

Eventually this would lead to the Meiji Restoration – a period of great industrialisation and social change within Japan. This period would be seen as a great modernisation for Japan, reversing many of the authoritarian rules of the Sengoku and Edo periods. Foreign trade and communication became more widespread and with it trade both into and out of Japan became normal.

The Meiji restoration had wide reaching effects but two major outcomes affected the population the most. Firstly the ruling of the country was returned to the Emperor and the Shogunate was abolished – in doing so the Emperor returned all feudal domains to Imperial governance and established the Prefecture system that remains in place today. Secondly he abolished the “four divisions of society’ that had affected social rule and structure during the Edo period. Throughout this period the Samurai and Merchant classes had strict rules governing the carrying of weapons, dress and the way money could be spent. To abolish the Samurai class the Emperor required all stipends paid to this class to be converted into government bonds and a conscription system was set up to establish a modern army.

At the time of the Meiji Restoration the geisha were in full swing, woodblocks were frequently painted of the most famous geisha and they were regularly influencing ladies fashion. Not only did the Meiji Restoration remove the wealth of many of the Samurai class who were patrons but Western dress started to influence Japanese Fashion. This marks the period when geisha stop being the most innovative fashionistas and begin to become bastions for traditional dress and custom.

The newly formed central government also began to create new edicts and laws as part of their effort for modern social change. Noting the ethics of the West and wishing to be seen as a moral and upstanding society an emancipation law was created in 1872 which forbade endentured servitude. That is it was no longer legal to sell young girls to brothels and geisha houses and women who had been sold to brothels at the time had their debt cleared. Despite the seemingly positive step for human rights many of the women were left homeless and unemployed and only 3 years later the law would be over turned. Prositution would not be outlawed again until the American occupation. The government still tried to make the geisha districts a more controlled and respectable affair. From 1886 geisha wages were set industry wide, customer records needed to be kept of fees and visitations and taxation was applied to the entertainment industry. Paperwork was no task for a geisha though and in 1895 the National Confederation of Geisha Houses was created and with it a set of rules of dress and conduct created by the geisha community.

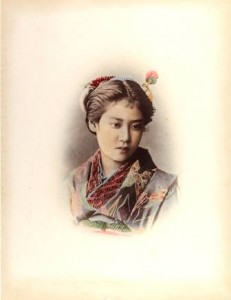

A coloured photographic postcard of Teruha a famous “Nine fingered geisha” popular in the Meiji period

Nonetheless it had become very common for business and politics to be conducted in teahouses and with many geisha being the only women educated enough to converse with worldly men they retained their popularity. With the return of the capital to Kyoto from Tokyo the Imperial court wished to create a Spring Festival and in response the Miyako Odori (Dances of the Old Capital) was created as one of the primary entertainments in 1875 – one of the rare opportunities for members of the public to see geisha and maiko perform. The merchant class now free from it’s Edo Period shackles was free more than ever to engage in geisha entertainments and the Sino-Japanese war caused more business meetings (and ozashiki) than ever. Geisha business was booming.

The invention of the camera and import into Japan also lead to an unlikely source of income – postcards, advertisements and calendars became wildly popular especially with the growing foreign tourists. The period even had it’s own geisha “it girl” Chisho Takaoka aka Teruha who was featured in many such postcards and became an international hit.

With such strong business and few legitimate careers for women in Japan at the time the Geisha population swelled enormously with over 25000 registered geisha by the turn of the 20th century.

Japonisme

Meanwhile the trade between Japan and Europe began to influence art and culture in the West. Japanese ceramics and woodcuts began to flow into European markets, a great fad for Japanese culture took over both Europe and America. This fad “Japonisme” quickly showed in theatre, fashion and art particularly French Impressionists. Ukiyo-e artists like Utamaro and Hokusai were all the rage in Europe and with it the exotic images of the geisha, actors and other characters of the pleasure and entertainment world. Famous artists like Toulouse Lautrec, Whistler, Renoir, Klimt, Van Gogh and Renoir would all fall under the influence of the newly found Japanese aesthetic.

Music and theatre began to portray increasing numbers of Japanese themes with composers like Puccini, Gilbert and Sullivan and Saint-Saens featuring Japanese culture throughout. These endure even today with Madame Butterfly and the Mikado appearing regularly on stages in the West. Businesses were established to bring Japanese artisans to the West. Famously Sadayakko Kawakami was a former geisha and consort to the Japanese Prime minister who would capture the hearts and minds of Western audiences when she toured the US and Great Britain. More about her story can be read in Leslie Downer’s biography.

Japanese gardens began to appear in Europe in the late 19th century and books on Japanese aesthetics and landscaping began to grow in popularity. Formal recognition of the style was given when a Japanese rock garden was exhibited in the 1939 Chelsea Flower Show.